BUFFALO, N.Y. — Western New York has a few brushes with severe weather each warm season, typically with high winds and some relatively large hail. But “large” in the Northeast is very different from “large” out on the High Plains.

A few weeks ago, meteorologists were officially able to confirm that a hailstone measuring 6.4 inches in diameter and weighing in at 1.25 pounds smashed into the ground in Hondo, Texas. Hail that size is estimated to fall at speeds over 70 mph. Yikes!

Hail that size is far more likely in any given year in the Plains than any other part of the country. The reason is that that region happens to be the perfect spot for all of the right ingredients for large hail to come together.

A garden variety thunderstorm needs three things to get going: moisture, lift and instability. In more simple terms, you need air with enough moisture, something to get that air to rise and something to keep it rising high enough to condense and form clouds.

RELATED: A recipe for thunderstorms

Severe thunderstorms need those three ingredients plus a little extra spice. The keys for large hail are a very energetic atmosphere, the right amount of wind shear and a pocket of dry air at mid levels of the atmosphere.

RELATED: The real shape of raindrops

Meteorologists measure the amount of energy in the atmosphere using something called Convective Available Potential Energy or “CAPE.” A high CAPE atmosphere typically has very warm, humid air at the surface and that air cools down quickly with increasing altitude.

Wind shear is just wind changing direction with height. A storm that forms in an environment with little or no wind shear can quickly “rain itself out” because the updrafts and downdrafts stay relatively close together. A moderate amount of wind shear can separate the two and allow the storm’s updraft to grow stronger and last much longer. A stronger updraft can hold hail up in the storm top longer and allow it to grow larger.

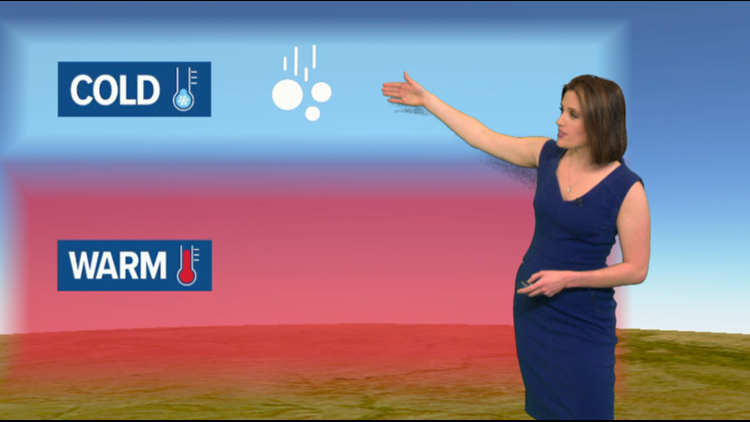

The dry air component sounds a little backwards. How does dry air make for larger pieces of precipitation? Turns out, the dry air doesn’t add to the hail, but it prevents it from melting on the way down. That’s because the dry air helps play host to a process called “evaporative cooling”. As precipitation falls, it evaporates into the dry air and cools it down. That makes a cooler path from cloud top to ground for the hail, again preventing it from melting and shrinking.

New episodes of Heather’s Weather Whys are posted to the WGRZ YouTube channel every Wednesday evening.

If you have a weather question for me to answer, send it to heather.waldman@wgrz.com or connect with me on Facebook or Twitter.