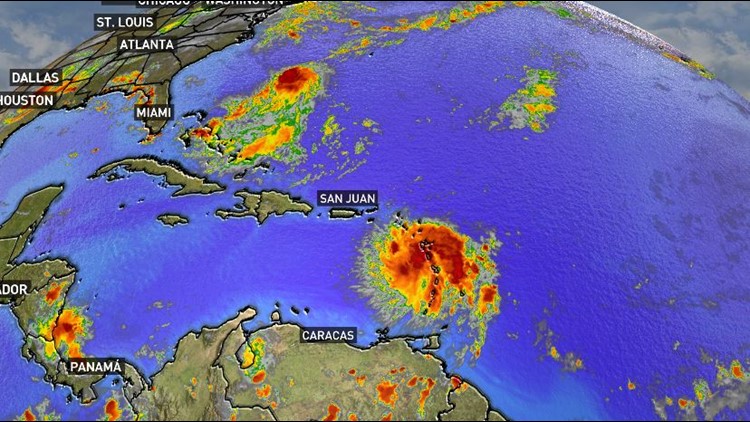

Tropical storm Dorian was churning its way through the Lesser Antilles Tuesday afternoon, set on a course towards a possible landfall in the Florida Peninsula this weekend. It's the fourth named storm since the season began almost three whole months ago, but more storms are likely to be named in the coming weeks as the Atlantic "wakes up" from its early summer dormancy.

This is not at all unusual. September and October historically produce the most named tropical systems out of the six month season. On average, the Atlantic season peaks on September 10. The first major hurricane — that’s a Category 3 or greater — historically forms on an average date of September 4.

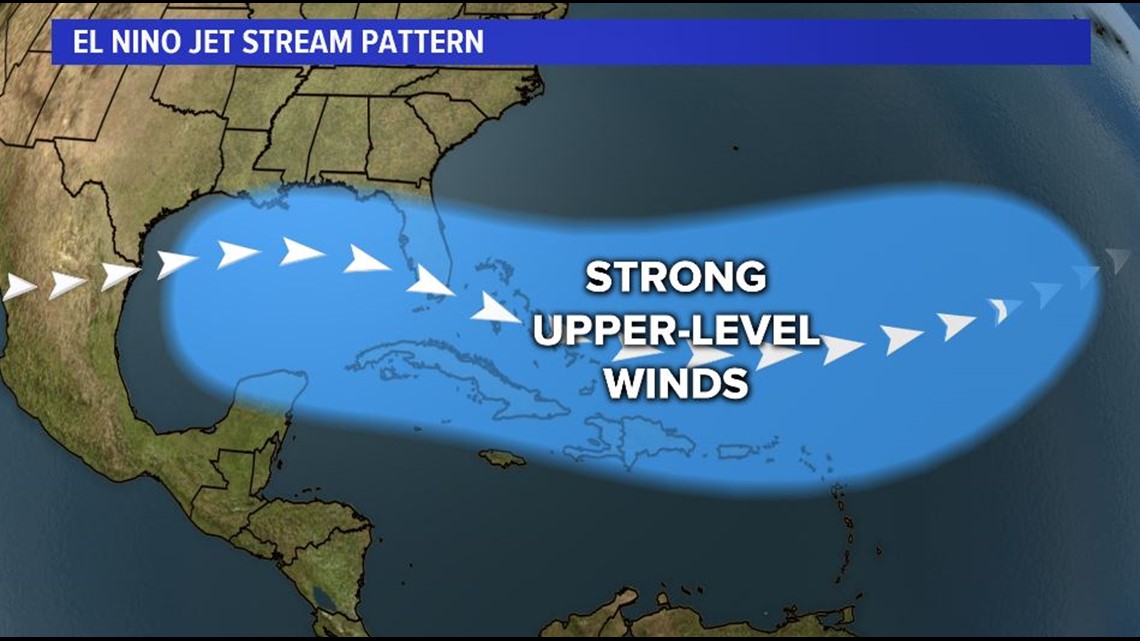

So far this season, atmospheric patterns have been dominated by an unusually strong southern flow in the jet stream. A weakening El Nino and the signature warm waters that come with it in the eastern Pacific created that shift.

When the jet stream is that far south, winds in the upper atmosphere are too fast for clusters of thunderstorms to grow and stay organized. The wind shreds them apart. Add in some extra dust from the Saharan desert and you’ve got a pretty hostile environment for tropical storms, even though the ocean temperatures are much warmer than normal.

But as El Nino weakens, atmospheric patterns are returning to more neutral positions. That means the jet stream is lifting back to the north, and the upper-level winds will weaken. That means a better chance for storms to bubble up over the warm Atlantic waters and stay organized long enough to spin into tropical systems.

The National Hurricane Center is now projecting 10-17 named storms by the end of November. At least four more storms should become hurricanes. A few of those may end up as major hurricanes.

Of course, it’s impossible to predict exactly where any of those may end up at this point, so anyone with an interest in the coastal US or the Caribbean should keep a close eye on things for the next couple months.