BUFFALO, N.Y. — You may see a low-flying plane over your house, several times, over the course of this month.

It's been brought in by the NY State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) to conduct a radiological survey of the Buffalo metropolitan area.

Bird of a different feather

Operated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency the plane, nicknamed ASPECT (Airborne Spectral Photometric Environmental Collection Technology) has all sorts of sophisticated gear, to detect chemicals, pollutants, ground radiation, and more.

Based in Texas, it can reach any point in the continental United States within nine hours if needed.

Often dispatched to emergencies, like this year's train derailment f a chemical train in East Palestine, Ohio, the DEC brought it in to conduct an airborne radiological survey of Niagara and Erie counties.

It is rather hard to miss, as it only flies 500 feet above the ground, which is roughly the same height as Buffalo's tallest building, the Seneca One Tower.

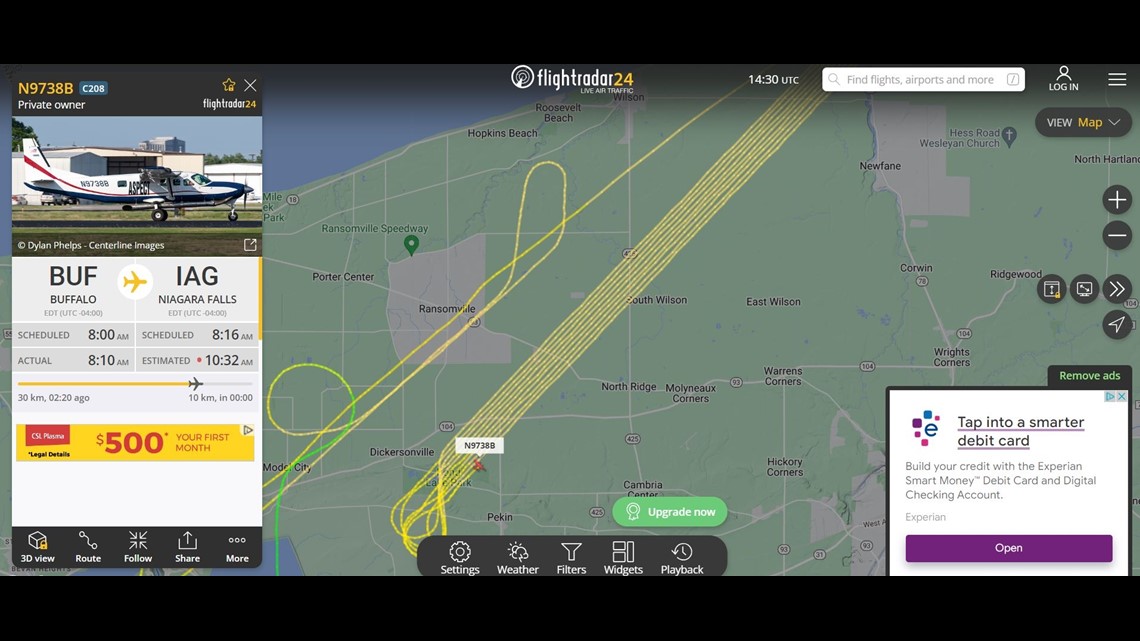

It began traversing the skies over northwest Niagara County on Monday flying in a precision path, much like a combine through a cornfield, and will continue to do so for the remainder of the month before its task is complete.

Radioactive hot spots are not uncommon, particularly in Niagara County, due to its industrial past where many companies engaged in the production of war materials, including atomic weapons.

An aerial radiological survey such as this has not been conducted since 1984. However, the sensory equipment has progressed significantly in the nearly 40 years since.

"Instead of the several dozen or 100 plus sites they found back then, they may very well find hundreds or perhaps thousands of hot spots," predicted Tom Tuori, a former environmental engineer who is now a practicing attorney specializing in environmental law with Harter Secrest & Emory.

Tuori predicted the next step for environmental officials, after the data from the air is analyzed, would be to then investigate areas of possible concern from the ground level.

"Probably the next step will to drive around on public roads, and do screening from the roadways," he said.

The likely tip off that your property may contain a "hot spot" would then be a knock on the door from DEC.

"Once they confirm a hotspot via that (surveying from the road) approach, then they will likely ask permission from property owners to sample and screen on individual properties." said Tuori, who noted the DEC's investigative powers would permit the agency's entry onto private land without the owner's consent.

"However, they usually try to gain entry without using means of compulsion," he said.

What happens if they find something?

The DEC stated in a press release: "This aerial survey is being performed out of an abundance of caution to provide the most current and scientific information ... to guide any follow-up on-the-ground surveys and sampling."

But if the presence of radiation is confirmed, and depending how severe, Tuori noted, "It's going to cause some problems unless someone cleans it up."

Although residential property owners would rarely be on the hook for remediation costs, which can easily reach millions of dollars, there are other potential issues for property owners.

"It could be tough to sell your property," Tuori said, noting that the findings of the DEC would be publicly disclosed. "It could impact your ability to do things like put an addition on your home. We had one client who had trouble because the stuff was underneath where he wanted to put the deck in."

The discovery of a hot spot, which is determined to be in need of remediation, can also pose difficulties beyond inconvenience.

"They have made people move out of the house while they did the cleanup," Tuori said. "For four or six months they were put up in a hotel or bed and breakfast, so that is a possibility depending on where the stuff is, and how high the levels are."

2 On Your Side also asked Tuori, who has represented several clients in Erie and Niagara counties with legal matters involving the environment, whether anyone could be ordered out of their homes and lose them entirely.

Here again, he says it depends on the potential danger of what is found.

"That kind of outcome may be driven by the budget the agency has, to deal with what they find," Tuori said. "In the scenario I talked about they had the money, and it cost millions, to clean up just a couple of residential properties and get the people back in their houses.

"But, if there's a hundred or a thousand of those then they might not have the hundreds of millions it would take to do the job. And then it might be cheaper to do what they did in part of Love Canal back in the day and just demolish the house and put a fence around it for a while. That may be what happens if there's not enough in their budget to clean up the properties they find."

While the owners of residential properties may not have to pay for cleanup, that is not always the case for the owners of commercial or industrial properties.

"The agencies have policies not to go after residential owners for the cost of cleanup and those policies do not generally apply to a non residential owner," Tuori said. "So, in theory, every non residential owner is potentially on the hook for a cleanup. They could be ordered to do it, or the agencies could do it and ask for some of the money back.

"They would also face the same kinds of problems residential owners would have ... an inability to sell, maybe trouble financing or doing an expansion or improvement ... even digging to do a utility line could be a problem depending where you dig and what you find."

.