IRVING, N.Y. -- Through the passage of time, events become distorted and even forgotten. In the case of Native Americans in the United States, much of their chronicles have been lost or deliberately unrecorded.

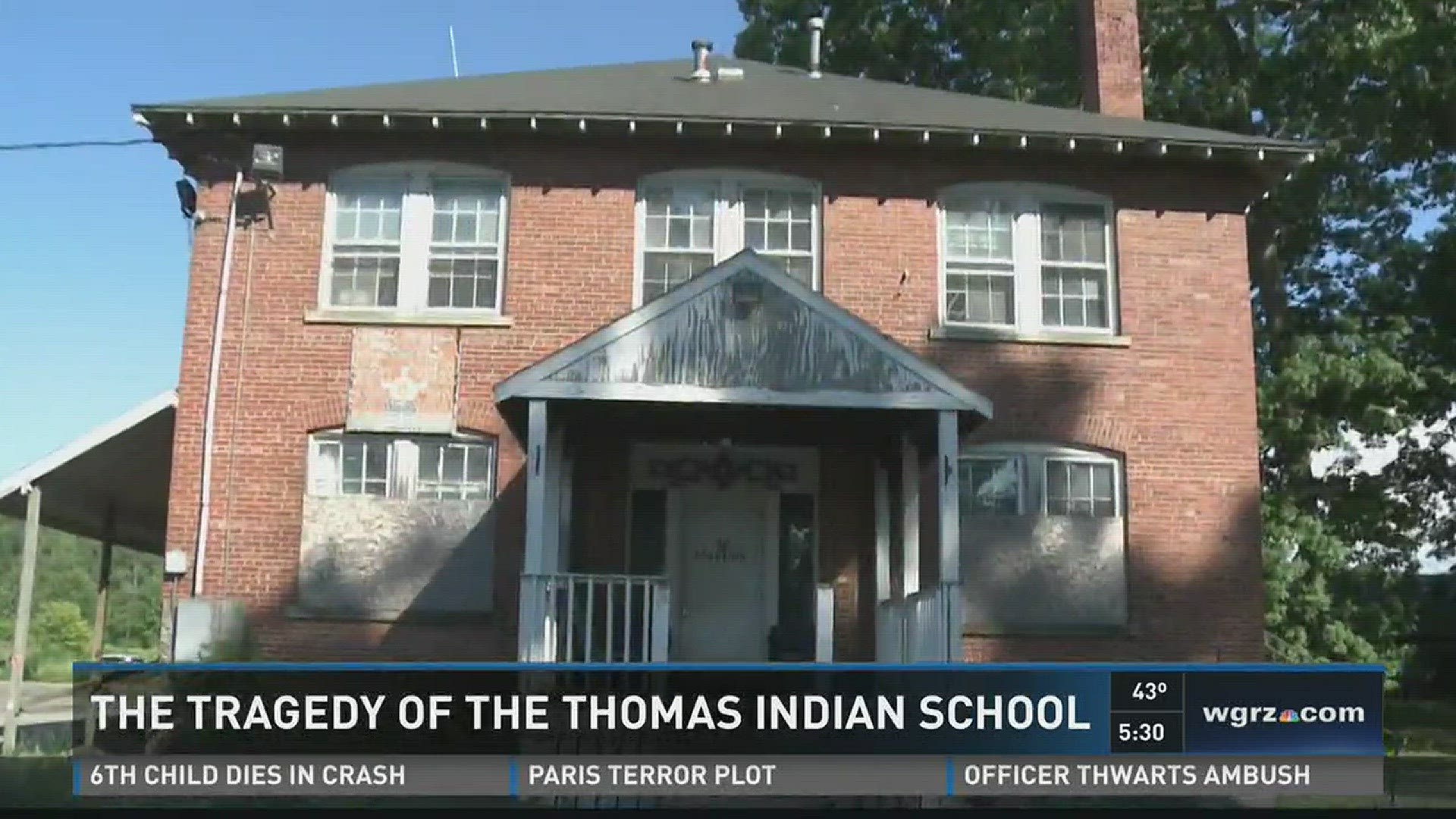

We in Western New York are as guilty as anywhere else, and the Thomas Indian School at the Cattaraugus Indian Reservation is a living testament to the folly of losing our shared history.

Keith Burich is the author of The Thomas Indian School and the "Irredeemable" Children Of New York.

"It's a story that needs to be told," Burich says.

"It's also a story that needs to be told for the children who went here, and their families. They need their story to be told, and their families need to know what happened here at the Thomas Indian School."

Indian Boarding Schools in the 1800's were widespread across the United States and Canada, and a direct result of the failing reservation systems. For many reasons, conditions on the reservations were brutal. Native people often fell to the many headed hydra of social ills from being forced to live as pariahs in American society.

Poverty, disease, alcoholism and domestic abuse ran rampant through their communities, forcing Indian families who were unable to care for their children to surrender them to boarding schools, or worse: having them taken forcibly by federal and state authorities.

Burich says the Thomas Indian School is still considered to be the worst of them all.

"The traditional structures, the traditional institutions for taking care of children who might be abandoned or orphaned or whatever, broke down, because you were attacking the communities and the families and they were no longer able to take care of their own. And so what do you do? You create institutions to take care of them, and that was what the Thomas Indian School was all about. The Thomas Asylum For Orphaned And Destitute Indian Children."

The school actually began as a somewhat benevolent institution. It was founded in 1855 by two Presbyterian missionaries, the Reverend Asher Wright and his wife, Laura. Indian children from across the state were taken in, including those from the Seneca Nation. At the time, the Wrights were still teaching the Seneca language and employing teachers who spoke Seneca and were sympathetic to their plight.

But that all changed when in 1875, the state Board Of Charities took over. David George-Shongo is Director of the Seneca Iroquois National Museum in Salamanca.

"When the state started taking over, they started making new rules, and changing," George-Shongo said.

"So you were no longer able to speak the language. Some people were forced to go there. Some people had good experiences, the majority of people didn't have good experiences."

For many of the children of Thomas Indian School, the experience was traumatic right from the beginning.

Elliott Tallchief was only five years old when a state social worker came to take him and his six year old sister away from their family.

"We were small. They just dragged us into the car," Tallchief recalled.

"We were crying and screaming too, I don't know, but I remember crying all the way. How do you get used to it, you know? The tears stop, and eventually you fit in. "

Carson Waterman turned five shortly after his admittance to the school. He says he learned some hard lessons at an early age, lessons that no child should have to learn.

"For me, after a number of years, you get used to it and you get toughened to it, and you think, well, I'm on my own, I'm the only person I can rely on."

Carson and Elliott both recall being punished for speaking Seneca. It was just the first step in stripping them of their culture in an effort to force assimilation to the American way of life.

George-Shongo recounted a particularly horrible experience.

"I had one cousin, I heard , they thought she had passed on. It was the middle of winter, the ground was real hard, and I guess there was a place in the attic where they would keep the kids that had passed on there until they could break the ground, and she wasn't passed on, she was in a coma, and she woke up, and all her friends were dead around her. "

Tallchief has his own bad memories.

"We used to watch movies on Saturday in the gymnasium, that's where we used to go for movies. They got us to the point where we used to cheer when the cavalry came, you know what I mean, to defeat the Indians."

"There was severe emotional and psychological effects from being treated as Indians," says Burich.

"From them realizing they were being punished for being Indians, and if they're punished for being Indians, there must be something wrong with being Indians, and therefore they're something inferior."

Many of the children were institutionalized at Thomas until they were legally able to leave, making them dependent on the rigid routine of the institution. They had no job, and often no family to return to.

If they did return to the reservation, it was to crushing poverty and the other numerous ills that plagued them. Others were simply lost. Very few were left unscathed.

Photojournalist Terry Belke asked Waterman if the school prepared him for outside life afterwards.

"No! Ha! I mean, where are you supposed to go? Leave? You know, there were very few jobs at that time."

"I look at the thing now, from the point when I was brought up here, to the point of when I quit," Tallchief wonders.

"I think about why they put us through this. To erase who you are, that was the point."

The Thomas Indian School closed in 1957, long after most other Indian boarding schools were shut down. Some of the buildings still stand, and for many of the children, the only trace of their existence are some names scrawled on an attic rafter in a decrepit dormitory and a few forlorn headstones in an all-but-forgotten cemetery across from the old school.

The repercussions, however, are still being felt in the Seneca Nation today. Communities were shattered, and their language is fading, despite efforts to teach it.

This is particularly damaging because traditional ceremonies use the Seneca language exclusively. This further hampers efforts to keep their proud culture alive.

New York has never taken responsibility for what happened, nor has the state issued an apology. Though the scars still run deep, the Nation remains strong, and continues to look to the future.

The motto was "kill the Indian and save the child." Tallchief says the school lived up to that motto, and it still takes an effect today.

George-Shongo remains optimistic.

"My Grandpa, he did teach me things that are Indian and stuff. He said if someone says something bad to you, he says, say nya:weh to them. In our language, nya:weh means thank you."

"You might think: why would he say that? You say nya:weh because it gives it back to them, and you don't carry it with you. It's up to you what you're going to carry, and what you're not going to carry."

A great source to learn more of this tragedy is Keith Burich's book The Thomas Indian School And The "Irredeemable" Children Of New York. You can see it here.