A jury decided Monday that a Missouri boys ranch was not responsible for a pair of brutal murders committed by two runaways in 2013.

The two-week trial revealed horrific details of the killings of Paul and Margaret "Sue" Brooks at their winter home in Stone County. The couple was only months away from celebrating their 50th wedding anniversary when two teens broke into the home.

Sue Brooks apparently had to watch her husband be killed, then fought for her own life as she was stabbed over and over again. An autopsy showed she was stabbed through her open eye and into her brain.

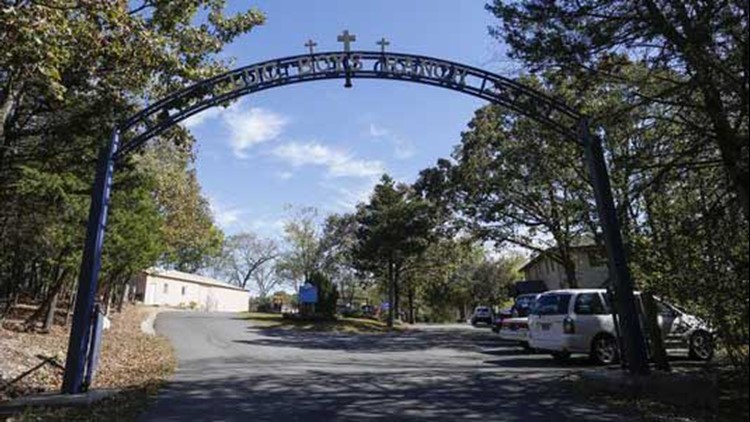

The killers were Chris Allen and Anthony Zarro, who had run away from Lives Under Construction, a Christian residential facility nestled in rolling hills just north of the Arkansas border.

Allen and Zarro are currently in prison for murder.

The family of Paul and Sue Brooks said Lives Under Construction should also be accountable for the murders.

After two years of litigation, a trial was held in late March in Lawrence County.

A lawyer for Lives Under Construction described the ranch as a transformative place for boys whose parents and society had given up on them. The lawyer said the ranch has helped hundreds of boys improve their behavior through hard work and the Christian faith — and by taking boys off their psychiatric medication.

The lawyer for the Brooks family painted a grim picture of the ranch, saying runaways, sexual abuse, burglaries and other crimes were commonplace, and that ranch leadership was well aware of safety shortcomings.

In closing arguments Monday, the lawyer, Randy Cowherd, said Lives Under Construction made three critical errors that led to the killings:

- The ranch was unequipped to handle Allen and Zarro, who were known to be dangerous and unstable;

- The boys should not have been taken off their psychiatric medication;

- The boys were not being supervised when they ran away.

Cowherd said that days before the killings, Allen's mother had questioned whether her son should be institutionalized.

Allen had also called himself "evil" and previously said he wanted to kill someone, Cowherd said.

According to Cowherd, Zarro, shortly before running away, said: "Take me to juvie (juvenile detention) or I will hurt someone."

Both boys had severe mental health issues and were prone to violence, Cowherd said.

Cowherd said that the ranch — whose founder's only degree was in wildlife management — should not have been accepting these boys.

In his closing arguments, the ranch's attorney, John Schultz, repeatedly told jurors that the case hinged on whether the ranch, its founder or his wife "directly" caused or contributed to the murder of Sue Brooks.

Schutz said the boys ran away from the ranch two days before the murders and broke into homes, pilfering drugs and alcohol.

The boys were high and drunk at the time of the murders, Schultz said, though Cowherd said there was no evidence to support that.

Schultz acknowledged that Sue Brooks had died a horrific death and that his clients were not perfect.

At one point in his arguments, Schultz stepped away from the podium, walked over to the ranch's founder, Ken Ortman, who was sitting at the defense table with his wife.

Schultz stood behind them and read "The Man in the Arena," a oft-quoted passage of a speech given by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1910 about a courageous man who has devoted himself to a "worthy cause."

"It is not the critic who counts... The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood," Schultz recited.

Schultz put his hand on Ortman's shoulder.

"That's Ken Ortman," Schultz said. "He is the man in the arena."

Lives Under Construction has had a "remarkable string of successes," Shultz said, by "swapping out the (psychiatric medication) for the love and the hugs... recreation, faith."

"What message is this going to send to the other facilities?" Schultz asked the jury. "Why would you do this job?"

Cowherd, the plaintiff's attorney, said there is a message to be sent to other facilities like Lives Under Construction: Follow the safety rules.

Cowherd compared Lives Under Construction to a car with no brakes.

It's a possibility that a car with working brakes will get into an accident, Cowherd said, but it's a certainty that car without brakes will crash.

For years, Cowherd said the ranch was told over and over again by the state of Missouri to not take boys off their medication without a trained psychologist or psychiatrist monitoring them.

Now, the ranch is no longer licensed by the state. Using an exemption for religious facilities, Liver Under Construction voluntarily gave up its licensure a few years ago.

That means less regulation and oversight.

"It's time to take responsibility," Cowherd told the jurors.

He asked them for a judgment between $7.6 million and $21 million.

The three sons of Patrick and Sue Brooks sat at the plaintiff's table throughout the trial.

About 50 people filled the courtroom's wooden benches for the trial's closing arguments Monday, which lasted more than two hours.

For almost the entirety of Monday's hearing, Michael, the oldest son, sat with his elbows on the table, his forehead resting on his clasped hands, his head bowed.

The jury went to deliberate at about 11 a.m.

People went outside the courtroom and milled about.

The Brooks family thanked the dozens of people who came to support them.

Michael Brooks went back into the courtroom and sat by himself.

In the hallway outside the courtroom, Ortman told the News-Leader that a multimillion-dollar judgment could mean the end for Lives Under Construction.

Ortman said his ranch's insurance only covers up to a $2 million settlement.

"Their intent this whole time was to shut it down and bankrupt (my wife) Sheila and I," Ortman said.

According to court documents, seven defendants originally named in the suit — the board members of Lives Under Construction — previously settled with the Brooks family for a combined total of $5.7 million.

After a little more than three hours of deliberation, the jury returned a verdict Monday in favor of Lives Under Construction.

As of October, 18 boys were residing at the ranch, which brings in about $1 million of annual revenue. Tax records show that revenue is almost entirely made up of donations and grants.

Lives Under Construction still faces three more lawsuits, which say boys at the ranch sexually abused each other for years, and the ranch covered it up.

The ranch denies these allegations.

One person went to prison for sexual abuse at the ranch. A 19-year-old resident raped his 9-year-old roommate in 2009. Court records show the rape went unreported to authorities for months.

Emails sent by Ortman and made public through the wrongful death lawsuit say juvenile officers removed multiple boys from the ranch for sexually assaulting each other.

Ortman told the News-Leader in 2017 he doesn't believe the 9-year-old was raped at his ranch, despite the rapist's admission and the boy's medical records.

Ortman said the boy's anal scarring must have occurred before he arrived at his ranch.