BUFFALO, N.Y. - 2017 is a milestone year for the New York Lottery.

Exactly 50 years ago, in 1967, the state-run lottery system launched here as a result of a constitutional amendment approved by voters. The decision, like any public referendum, did not come without controversy. The idea of state-sponsored gambling troubled many, including those who argued it would prey on disadvantaged people in poor neighborhoods.

To sway voters, though, the New York Lottery made a promise: proceeds from the lottery would help fund the state education system. Schools across the state, from Buffalo to the Southern Tier to New York City, could benefit financially from the sale of lottery tickets. Voters -- enough of them, at least -- seemed to like the compromise.

The New York Lottery's original slogan? Your Chance of a Lifetime to Help Education. Even the harshest critics of the lottery would have trouble arguing with that sentiment.

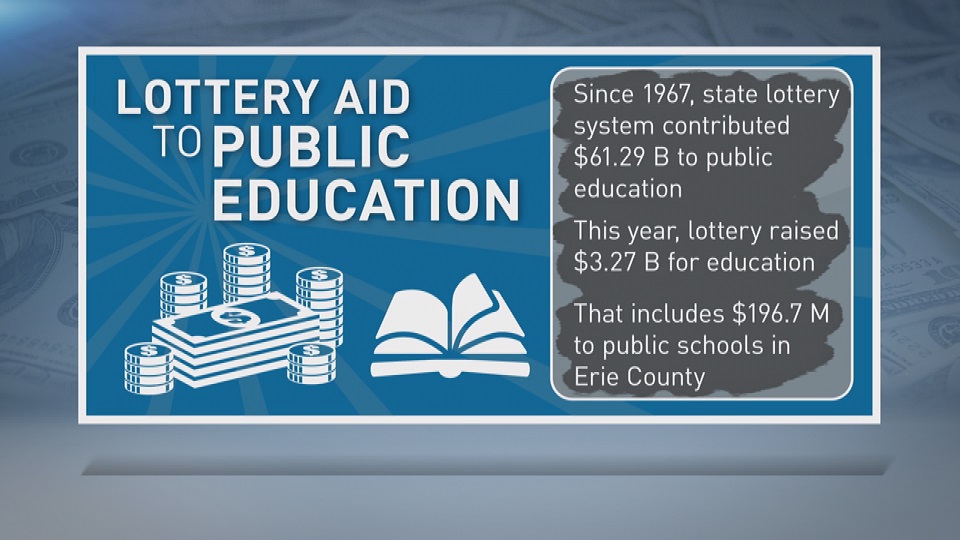

Five decades later, there's no denying the New York Lottery has helped fund public schools across this state. The numbers, on the surface, seem staggering. According to state data, lottery proceeds have contributed $61.29 billion to public education since the inception of the system in 1967. In 2016-17, the lottery raised $3.27 billion for education, including $196.7 million in Erie County alone.

The New York Lottery still proudly touts its contribution to schools, just as it did in its original slogan. A few years ago, you might remember seeing a mildly famous television commercial featuring a group of singing kids: "Every time you play a New York Lottery game, a portion of your sale goes to support New York state schoolchildren," the announcer says on the screen.

Nothing you hear from the New York Lottery is wrong, or even misleading. The lottery raises billions of dollars in school aid every year as a result of its profits, just as it was designed.

But that has never satisfied everybody. For decades, the lottery has been targeted constantly by fierce critics, who argue the state has never used the lottery proceeds to its full advantage. The common argument is that the state relies too heavily on lottery money -- using it as a crutch, essentially -- and doesn't invest additional funds for schools.

The argument has seemed to pop up everywhere over the years. It came up during the gubernatorial campaign in 1994 between George Pataki and Gov. Mario Cuomo. In 1998, state comptroller Carl McCall called the lottery's additional aid to education a "myth." Numerous national media outlets have included New York in their examinations of state lottery systems; even John Oliver ran the New York Lottery's schoolchildren commercial during his HBO show in 2014.

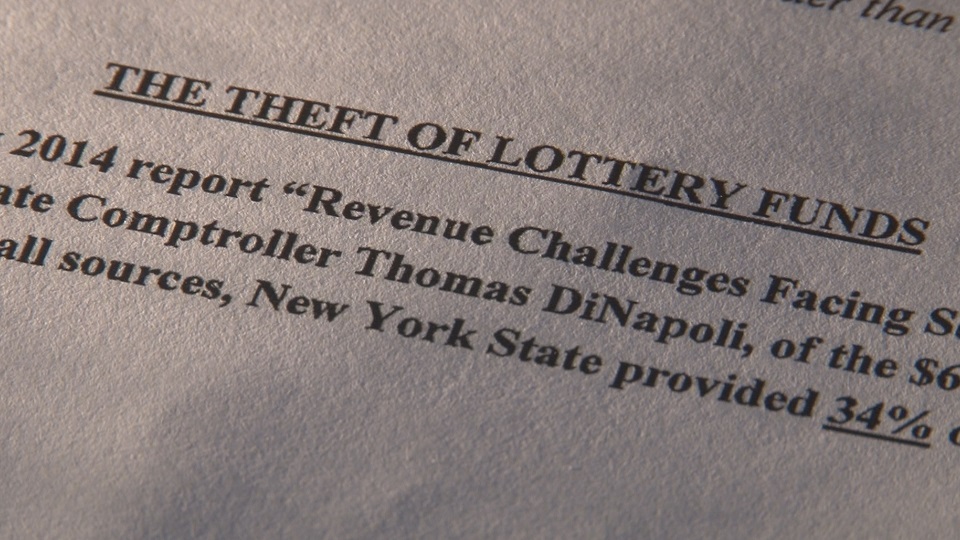

As recently as this March, Buffalo Teachers Federation President Phil Rumore wrote a report to state lawmakers, in which he included a section titled, "The Theft of Lottery Funds." In that section, he cites McCall's report from 1998, as well as a report from current comptroller Thomas DiNapoli, showing that the state's investment into education as a percentage of its overall budget had dropped over the past few decades.

"It's just a ruse. It's a shell game," Rumore said. "They're saying, 'well, we're gonna take this money here, it's all gonna go to education. But we're gonna pull back on our share.' They're basically robbing our students."

About 33.8 percent of the lottery's revenue in 2016-17 was directed to education, according to state data. The majority of the revenue goes toward prize money, although all leftover profits are earmarked for education.

A spokesperson for the New York Lottery declined an on-camera interview, but he provided a few key details that are important to keep in mind in the midst of the criticism. First of all, the latest state budget increased education aid by $1.1 billion, bringing the total state investment to an unprecedented $25.8 billion. School spending has soared by $6 billion over the past six years. That's critical to consider, especially because many other states have been criticized for decreasing education spending despite the existence of lottery funds.

In New York, it wouldn't be a stretch to say that lottery funds probably prevent an increase in taxes. Comptroller DiNapoli said so himself in a report about the lottery system in 2014: "Increased revenue driven by Lottery expansions has allowed State policy makers to provide additional funding for public services without imposing additional taxes or fees."

But Rumore, citing a New York State Court of Appeals decision from 2006 that led to the creation of the Foundation Aid system, still believes the state owes schools much more money as a result of that lawsuit. And he believes the lottery plays a big factor, since that revenue is distributed by the same income-based and size-based formula as other education aid.

It should also be pointed out that lottery money made up only 14 percent of total state aid to school districts in New York last year.

"They can say that every penny from the lottery goes to education," Rumore said. "But the dirty little secret is, it's using to supplant money."

State lawmakers have made similar arguments for years. Two Western New York representatives from totally opposite ends of the political spectrum -- Senator Tim Kennedy (D-Buffalo) and Assemblyman David DiPietro (R-East Aurora) -- are both pushing legislation in Albany to make changes to the lottery system and its impact on education.

Kennedy is the sponsor of a bill in the Senate to increase the percentage of lottery revenue directed to education, offset by a decrease in the percentage of money devoted to prizes. The percentage of prize money generated from games like Mega Millions and Powerball, for example, would drop from 55 percent to 45 percent under Kennedy's legislation. In turn, education revenue from other games would jump from 45 percent to 50 percent. Scratch-off tickets would increase this education percentage from 20 percent to 40 percent.

Overall, Kennedy says the slight changes to the formula will result in $880 million in additional revenue for education across the state, including an extra $51 million in Erie County.

"It's actually specifically written to say that the change in the equation -- any new funding -- will go directly into our children, and their education, and their futures," Kennedy said. "We're dealing with an equation that was put in place 50 years ago. It's about time New York state gets in line with the 21st Century."

Assemblyman DiPietro is listed as the multi-sponsor on a bill that would prohibit lottery revenue from being used for any non-educational purpose.

"The lottery was supposed to fund education. And now we're looking at a small percentage that actually goes to education," DiPietro said. "Everything gets co-mingled into the general fund, and then dispersed, and they take the money out and pay these special projects. And they call it 'education funding.' And it's really not. That's what we want to tighten up."

The New York Lottery's spokesperson said the agency cannot comment on proposed legislation.

Rumore, however, sees the proposals as partial solutions to a much larger problem within the public school system.

"That's a step in the right direction, but they really need to start addressing the inequities of the funding for poor school districts, not just Buffalo, but rural school districts," Rumore said. "The inequities in the funding between rich and poor really shouldn't exist."

Both bills proposed by Kennedy and DiPietro would need to be approved by their respective committees before the full Senate or Assembly could vote on them.

DiPietro's Assembly bill is in the Ways and Means committee.

Kennedy's Senate bill is under consideration by the Racing, Gaming and Wagering committee.

"Your chance of a lifetime to help education. We believe that promise -- although it's been met -- has only been met in part," Kennedy said. "And we can do a heck of a lot better."