BUFFALO, NY – In the wake of growing concern over heroin deaths related to addictions which begin with prescription pain killers, some living which chronic pain believe the stigma associated with their medications has left them feeling like “collateral damage” in the heroin epidemic.

“Until you experience chronic pain, you have no idea what it’s like to live with it,” said Dawn Curto of Tonawanda.

Curto, who suffered a debilitating back injury when she got out of bed one morning in 1998, then experienced a host of associated maladies which finally resulted in her giving up her job as an respiratory therapist in 2006.

“You get tired of sucking it up. You get tired of smiling and grinning and bearing it," she said.

A Lifeline to Limited Function.

The pain medications Curto has been prescribed keep her out of agony, and provide enough relief for her to exercise some normal functions.

Yet, she and others in chronic pain still find themselves having to parse out what bit of energy they have left, to do the simple things most people take for granted, such as getting dressed, preparing a meal, or shopping.

“I’m lucky,” she insisted. “Some people in my condition are unable to even walk a few steps.”

However, she says there is a stigma associated with her need for medications which have come under scrutiny in the past few years, and their association with addiction which has increasingly lead to tragic results.

Collateral Damage.

“This scrutiny can come from even your friends and family let alone strangers,” she said.

“Those of us who take these medicines responsibly are being persecuted in a way…we are the collateral damage of the heroin epidemic."

One example of this, she says, was what happened after the arrest last year of Amherst pain specialist Dr. Eugene Gosy.

Gosy was indicted on federal charges of illegally distributing pain killers.

Following his arrest, his clinic was temporarily shut down, leaving thousands of his patients, such as Curto, in a lurch with no place to turn.

“There was no forethought to the patient abandonment," Curto said, adding that it took weeks before she was able to find another doctor to deal with her pain.

“His patients were stigmatized because other health care providers believed they were addicts,” she insisted, “and they are also afraid it will bring attention and direct scrutiny to them."

Dr Christopher Kerr of Hospice Buffalo was one of three physicians who scrambled to get Gosy's clinic back up and running in order to tend to his patients.

"It was short sighted from a public health standpoint because lives were going to be at risk,” Kerr recalled about Gosy’s arrest, which resulted in the sudden closure of his clinic.

He also concurred that the arrest of Gosy might have left other doctors feeling gun shy about treating patients in the manner they had been accustomed to, while causing other doctors who were considering specializing in pain management to take pause.

“They were all looking at what happened to Dr Gosy,” he said.

In the year since, the clinic once operated by Gosy has added a division of chiropractic and mental health therapy in an effort to -where appropriate-provide alternatives to narcotics.

While Curto says she was never addicted to pain killers, Jay Duderwick of Buffalo now believes he was.

Falling Through the Cracks.

Duderwick herniated a disc in his back while working out 30 years ago.

For 28 years he took over the counter medication until it caused a bleeding ulcer.

Physical therapy was unable to solve increasing complications from his original injury, so about two years ago he began taking prescription pain pills.

He worried almost from the start about taking opioids, having heard so many stories about them and their association with addiction on the news.

He also was worried about his own behavior as a result.

“It made me feel like some sort of drug addict,” he recalled. “I was calling up my doctor all the time to get my prescription re-filled and thought to myself, ‘what have I become?’ It really bothered me.”

It was enough to make Duderwick opt for surgery on his back, which was performed three months ago.

However, because the surgery was supposed to cure his pain, he was denied any more of the prescription medicine he was taking.

He has since withdrawal symptoms, including nausea and an inability to sleep at night.

“I’m pretty committed to tough this out,” he said, while noting that there are plenty of others who might not be able to do that.

“If you know that if you can take another pill and all these (withdrawal) symptoms can go away…you don’t know how attractive that is at times when you're feeling so lousy,” he said.

The experience has left Duderwick feeling as though he “fell through the cracks” and he can’t help but wonder how many others there might be.

“There should be a system in place to encourage people of alternative ways to get off opiates and if they do, there should be help involved so that it’s successful. That wasn’t available to me. I was kind of told, ‘here you go…good luck’,” he said.

A New Alternative?

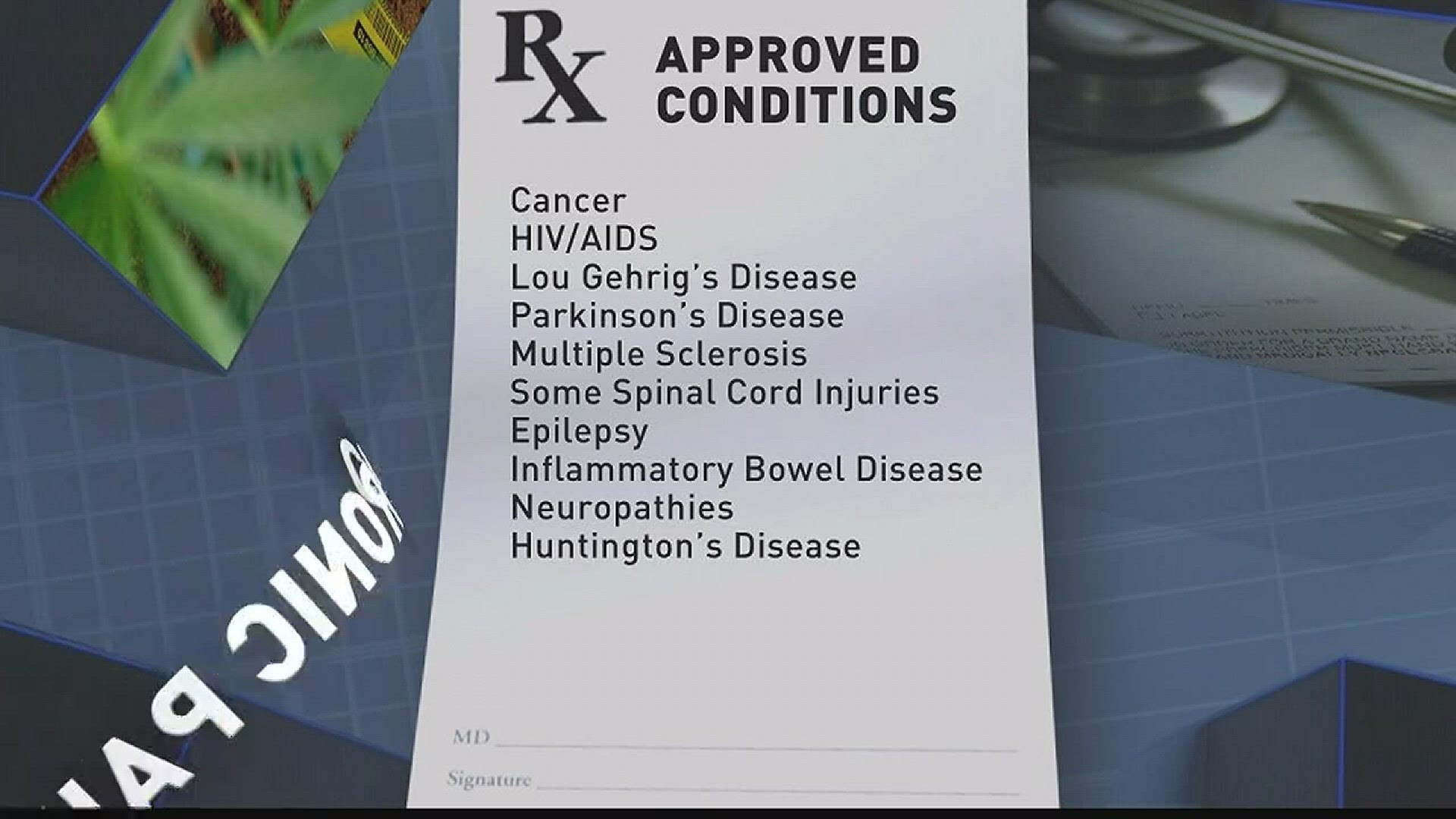

Three months ago, in a decision largely driven by the opioid crisis, the state health director added “chronic pain” to the list of ailments eligible for treatment by medical marijuana.

But obtaining it isn’t easy.

The process of becoming eligible to use it is cumbersome, the number of state approved dispensaries are limited, and insurance does not cover medical marijuana which can cost hundreds of dollars per month out of pocket.

Moreover, patients aren't the only ones who have to jump through hoops to participate in the state’s medical marijuana program, as evident by what Duderwick spinal surgeon has told him.

“My doctor was going to apply to be eligible to dispense it, but there was - I think he said- a 20 page application on line that would take hours to complete and he thought it was ridiculous and time consuming and told me he wasn’t going to go through all of that, " Duderwick said.

There, But For The Grace of God…

Beyond her firm belief that, unless you live with chronic pain you have no idea what it's like, Curto believes there's another thing that just doesn’t dawn on anyone.

That by quirk of fate and without warning, you could end up in the same boat as she and countless others have.

“No. Absolutely not," she said. “Nobody thinks about that. Why would you?”