![635512201624378225-Gas-Line-WEb-BG[ID=18801799] ID=18801799](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/fb89146016ed03a41bb789e87ee5977b56b782d8/c=441-13-1686-1077/local/-/media/WGRZ/WGRZ/2014/11/10/635512201624378225-Gas-Line-WEb-BG.jpg)

![Hidden Dangers: Old gas pipes pose underground threat[ID=18839581] ID=18839581](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/86d8b4e84e96c34257e92e40af99358c272eb9b9/c=0-44-600-557/local/-/media/WGRZ/WGRZ/2014/11/10/635512200163999018-Gas-Line-WEb-BG-600x600.jpg)

![Introduction [ID=18533339]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/embed.jpg)

A danger buried beneath our streets has resurfaced: thousands of miles of high-risk natural gas pipeline that cause destructive leaks every other day in the United States.

In the past decade, more than 1,700 significant gas leaks have killed at least 135 people, injured 600, and caused billions of dollars in damages nationwide. And these numbers don't include the tens of thousands of hazardous gas leaks that were caught before disaster hit. Leaks that could have been avoided.

Often times, a gas leak is out of the utility company's control. Things like construction, shifting earth and weather can lead to leaks. But some of these more destructive leaks are caused by aging bare metal pipe—pipe that the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration has been pushing gas utilities to replace.

"The older types of pipeline—the cast iron, the bare steel—are known to fail more often because of things like corrosion and ground movement, especially on the east coast where [things] freeze and thaw," said Carl Weimer, the executive director of National Pipeline Safety Trust.

There are at least 85,000 miles of aging cast iron and bare steel gas lines still lurking beneath American cities and towns, and most of those cast iron mains are in the Northeast.

"New York, Massachusetts, [and] New Jersey have thousands of miles of that old pipe," said Weimer. "It's known that it gets old and brittle and leaks and causes tragedies like we saw in New York City this past year."

![Chapter 1 [ID=18533499]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/embed.jpg)

On the morning of March 12, 2014, an explosion leveled two apartment buildings in East Harlem, killing eight people and injuring 48 others.

The cause was a 127-year-old gas main that sprung a leak. Tests of the soil in the area found natural gas levels as high as 20 percent, and federal investigators suspect the connection between a bare metal pipe and a plastic pipe is behind the blast.

The city's top utility company, Con Edison, received a call reporting a leak around 9 a.m. that day, but by the time the truck arrived two minutes later it was too late.

"If you live in one of those older East Coast cities that have hundreds of miles of cast iron pipe, that's just a failure waiting to happen," Weimer said.

Now, Con Edison and other utilities around the nation are speeding up efforts to replace cast iron and bare steel pipelines. But it won't be cheap.

It can cost at least $1 million per mile to replace aging pipe.

Con Ed's company spokesman Allan Drury said it will cost $215 million to replace about 65 miles of bare metal pipe a year. Replacing all of the utility's aging lines would cost as much as $10 billion, and much of that expense would fall on customers.

"It was obvious that not enough was being done to replace that pipe because there's huge costs with digging up old pipe and replacing it," Weimer said. "It's obvious that they're not getting it out of the ground quick enough."

And some worry it's only a matter of time before a big leak happens in their community.

![Aging gas pipes endanger communities across the country[ID=15788653] ID=15788653](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/a934fd896f349221375cf2b73908d272e75fbb8b/c=549-0-3960-2916/local/-/media/USATODAY/USATODAY/2014/09/17/1410985013001-02-GAS-PIPES.jpg)

![Chapter 2 [ID=18534407]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/embed.jpg)

Last January, Angela Babiak smelled natural gas near her home in Elma, NY.

"I called in and reported a natural gas emergency because it's just a very scary thing," Babiak said. "You don't know with a gas leak what's going to happen."

Within 15 minutes, National Fuel sent someone out to investigate. Babiak said she watched the representative walk around her front yard with measuring tape before sticking a device in the soil to measure the gas. Then she told Babiak what she found.

It turns out there was a 40 percent gas leak between Babiak's property and the neighbor's. But since it was at street level, the leak was put on a waiting list for repair.

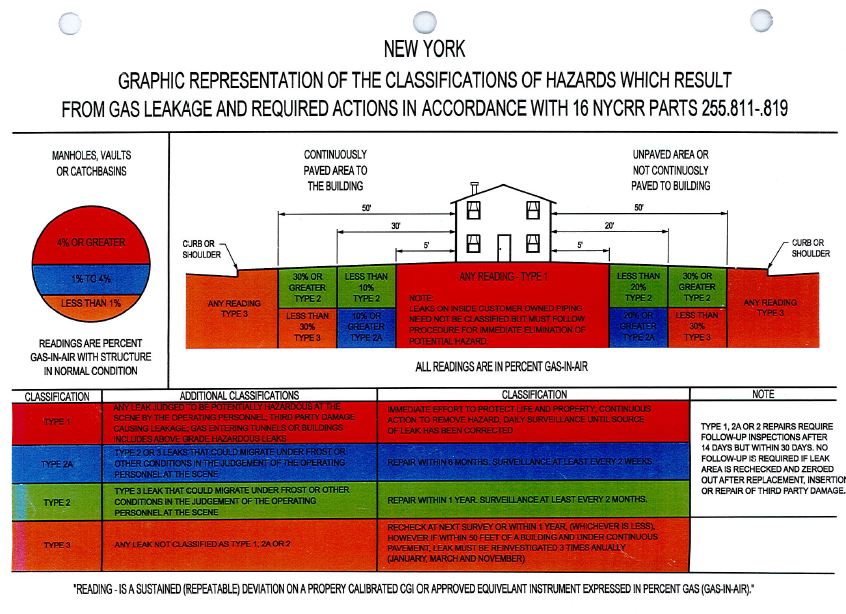

"Every leak is not necessarily hazardous," said Bob Plewa, the district manager of National Fuel. "The way in which leaks are classified are based on proximities to buildings and levels of gas readings."

According to National Fuel, the utility classified the Babiak's leak as Type 3. Unlike Type 1—a leak within 5 feet of a structure that must be repaired immediately—a Type 3 leak can take up to a year to fix. Anything Type 2, a leak within 50 feet, is repaired within 6 months.

"If we have a small leak within five feet of a building, it is an issue," Plewa said. "It is a hazardous leak and it does require an immediate response… but that same leak 35 feet from a house, because of the further proximity from the house, doesn't have the urgency."

Fortunately, National Fuel fixed this leak within two weeks. But Babiak isn't sure if the repair is permanent.

"For all I know they put a Band-Aid on a big problem," she said.

That big problem is a bad connection between a bare metal line and a plastic pipe. In 2005, before the Babiaks moved into their home, National Fuel replaced a 500 foot section of the leaky steel main with plastic. But the rest of the street stayed the same.

"In a matter of [a few] years that connection that they had made between the plastic and metal had already begun to start leaking," Babiak said. "They were piecing things together down one street. Why wouldn't you just do the whole street at once?"

![Chapter 3 [ID=18534739]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/embed.jpg)

So how do you know if there are bare metal gas mains in your neighborhood?

When asked if there is a map available of where bare metal or plastic piping is located in Western New York, National Fuel said their engineering department maintains maps, but they're for the utility only.

"Certain documents we like to keep internally," Plewa said. "I guess it's not necessary for the general public to know how our system wanders or travels down the pipeline or down the streets in the neighborhoods."

National Fuel also cited "security concerns" as a reason for withholding that information.

![Bob Plewa, District Manager at National Fuel [ID=18804217] [ID=18804217]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/pullquote.jpg) Click Here for an interactive map of Gas Lines in the US Of nearly 10,000 miles of main lines in Western New York, more than 2,000 miles are bare metal. Roughly 350 of those miles are cast iron.

Click Here for an interactive map of Gas Lines in the US Of nearly 10,000 miles of main lines in Western New York, more than 2,000 miles are bare metal. Roughly 350 of those miles are cast iron.

"Without a doubt there is quite a bit in the city, but there are a lot of rural areas too that still have bare steel," Plew said. "It's spread across our system of Western New York."

A good rule of thumb when it comes to guessing the age of a gas line is to learn when the neighborhood was developed. If it was prior to 1970, it is likely that the lines are bare steel whereas a newer town might have mains made of coated, protected steel or plastic.

"We've got some pipes within our system that's closing in on 100 years old," said Plewa.

Unfortunately for prospective homeowners, a real estate agent won't have the answers about the potentially dangerous gas line in front of the home.

"It seems unfair, but there's no way the home-inspector can check on the gas line at all," said Susan Lenahan, a real estate agent with MJ Peterson. "It's only the gas company that has that information."

![Chapter 4 [ID=18534819]](/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/embed.jpg)

"Most all of the states have now passed ways for the companies to do this on a faster basis," said Weimer. "But we're still talking 10, 20, even 30 years in some states to get all of the cast iron out of the ground."

In Western New York, National Fuel is required to replace at least 95 miles of unprotected pipeline a year, including both bare steel pipe as well as cast iron gas mains. At this rate, it will take more than 20 years to replace all bare metal mains.

Until that happens, utilities are sending people out to patrol old pipes for leaks, especially in the winter. That's because frost can not only crack bare metal pipes, but also create pockets of trapped gas if there is a leak.

"The frost more or less serves as a cap layer in which any leaking gas or any gas that may have been leaking because of the frost hits that cap and begins to spread out until it finds an area where there isn't any frost," Plewa said.

![Frost Effects on Gas Lines[ID=18803983]](http://bcdownload.gannett.edgesuite.net/wgrz/34300055001/201411/2489/34300055001_3884565264001_frost-gas-line-vs.jpg?pubId=34300055001)

Last winter, National Fuel had more hazardous leaks in Western New York compared to previous winters because the frost reached down to the gas lines, which are typically buried 30 inches underground.

"We had one of the coldest winters we had in probably close to 20 years," Plewa said. "The frost did penetrate down to the level of the gas mains."

So the utility sends people out monthly during the frost to survey pipes for leaks. When it's not frosty, plastic pipes are surveyed every 5 years and any old piping in business districts is surveyed annually. But bare metal lines outside business districts are looked every 2 and a half years instead.

The plan now is to replace all bare metal gas lines in Western New York with plastic piping by the year 2040.

"Plastic is the best, but out of the metal (steel versus cast iron) I would rank them equally the same. They each have their positives and their negatives," Plewa said. "But the bottom line is we'd like to replace them."

![Carl Weimer, executive director of National Pipeline Safety Trust--If you live in one of those older East Coast cities that have hundreds of miles of cast iron pipe, that's just a failure waiting to happen.[ID=18533859] ID=18533859](https://presto-wgrz.gannettdigital.com/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/pullquote.jpg)

![635509761363953863-Chart [ID=18666503]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/-mm-/965a2fec39369f1f25bf5aaace38a6fa582808b6/r=500x362/local/-/media/WGRZ/WGRZ/2014/11/07/635509761363953863-Chart.JPG)

![Gas Pipline Map[ID=18810069] ID=18810069](https://presto-wgrz.gannettdigital.com/Portals/_default/Skins/PrestoLegacy/CommonCss/images/embed.jpg)