By Joseph Spector, Sean Lahman and Frank Esposito, Albany Bureau

ALBANY - Halmar International did not have a state construction contract since 1988.

But that soon changed.

The Nanuet, Rockland County-based construction firm started to donate to Andrew Cuomo's election campaigns.

It gave $10,000 just prior to Cuomo's first win in 2010, and $135,000 overall in his eight years in office.

The company has since landed $236 million in state construction projects, plus a multitude of projects through the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, including a 23 percent stake in the massive $1.8 billion Long Island Railroad expansion, state records show.

While Cuomo denies any quid pro quo, similar examples are found throughout state government after he amassed one of the largest campaign funds of any Democratic governor in the nation.

As Cuomo seeks a third term in November, a review of records by the USA TODAY Network's Albany Bureau found Cuomo's campaign coffers are filled with donations from companies with business before the state — and regularly made through a massive loophole in state law.

The influence of money on New York politics is important: Taxpayers are often the ones on the hook for contracts and benefits awarded to donors.

The review's findings include:

- In all, Cuomo raked in $100 million in campaign contributions since he first ran for governor in 2010, surpassing any governor in the country who hasn't self-funded at least some campaigning.

- Cuomo's campaign cash is a complex web of influential leaders and companies, with 19 companies alone receiving $13 billion in state contracts after contributing more than $425,000 to Cuomo since he took office.

- Cuomo has relied almost exclusively on big donors, with 80 percent of his money coming from those who have given him $10,000 or more. In fact, 44 percent of his money came from those who gave at least $50,000, and nearly $17 million came from a mere 128 donors.

- The haul came, in part, through New York's biggest campaign-finance loophole: the ability to create limited liability companies to skirt donation limits.

- Since taking office, Cuomo received 20 percent of his money from LLCs — the most being from 16 set up by real-estate giant Glenwood Management that pumped $1 million into Cuomo's war chest. The company was embroiled in two corruption scandals involving top state lawmakers.

"The governor uses every conceivable measure to leverage his power to raise money," said Blair Horner, legislative director for the New York Public Interest Research Group, a good-government group.

"That’s the way the system is set up — and he uses it to the tune of $100 million."

Center of scandal

The extraordinary sums raised and spent by Cuomo have come with benefits and peril.

He was able to spend more than $25 million on his blowout Democratic primary victory last month against Cynthia Nixon, the actress who spent only about $2.6 million.

And Cuomo still had $11.6 million to spend on his general election race against third-party candidates and Republican Marc Molinaro, who had less than $1 million in his coffers in July.

Cuomo was down to $9 million in the bank this month, while Molinaro had just $211,000.

But the money raised has also been at the heart of criticism from his foes, who accuse Cuomo of being beholden to special-interest groups and major donors.

Not only that: The fundraising also has been tied to criminal convictions.

In July, Cuomo announced that he would donate $500,000 in campaign contributions received from upstate New York developers tied to corruption cases involving his former top aide Joe Percoco and Alain Kaloyeros, the former president of the SUNY Polytechnic Institute.

Percoco was convicted and sentenced in September to six years in prison for accepting bribes from the developers in exchange for using his influence to steer contracts to them.

Kaloyeros is set to be sentenced later this year after being convicted of bid rigging involving some of the same developers.

Cuomo "has allowed the trading of taxpayer support for political contributions. And it’s not only eroding faith and trust in government, but it’s defrauding taxpayers," Molinaro, the Dutchess County executive, said.

Cuomo has sought to portray Molinaro as the one with the pay-to-play record.

He cites in campaign ads that Molinaro's wife was employed by a former donor whose company got tax breaks from the county industrial development agency. Molinaro disputes any correlation.

Donors and their contracts

Cuomo and his donors deny any connection between contributions and government help, and Cuomo's office is quick to point out that he was not implicated in any of the corruption scandals.

"The governor has received contributions of all sizes from thousands of people who support his progressive agenda to improve the lives of all New Yorkers," said Cuomo campaign spokeswoman Abbey Collins.

"No donation of any size influences any government action — period."

Halmar did not respond to requests seeking comment about its campaign contributions to Cuomo and its state contracts.

Time and again, Cuomo's top donors have close ties to either the governor or his administration.

Take one of them: Cablevision, the Long Island-based cable giant.

It has given Cuomo $562,000 since he took office, employed Percoco after he left the Governor's Office in 2015 and benefits from lucrative tax breaks at Madison Square Garden.

The company's executives also donated to Cuomo, as well as paid for lobbyists to fight bills in Albany that would hurt its business, such as creating a utility consumer advocate and requiring standardized billing, state records show.

In another example, CHA Consulting, which was founded in Albany as Clough, Harbour & Associates, gave Cuomo $196,000 since 2010.

After a $50,000 donation in May 2014, it landed $15 million in state contracts, records show. It is also the project engineer for the massive Riverbend project in Buffalo, where Cuomo has committed $1.5 billion for redevelopment.

There was another tie: It too hired Percoco briefly after he left state office.

Then there is the Nixon Peabody law firm founded in Rochester.

It has made a whopping 137 separate contributions to Cuomo over the eight years, averaging about $1,200 each for a total of $164,000.

The firm has $7 million in state contracts, records show, and also handles the lucrative bond payments for the MTA — which is run by a board controlled by Cuomo.

"We have a number of offices in New York state and a number of our lawyers have varying interests in the political process, supporting diverse candidates and officials for many offices and across party lines," Nixon Peabody said in a statement.

A wise investment

Cuomo's donors extend heavily through the real-estate and building sectors.

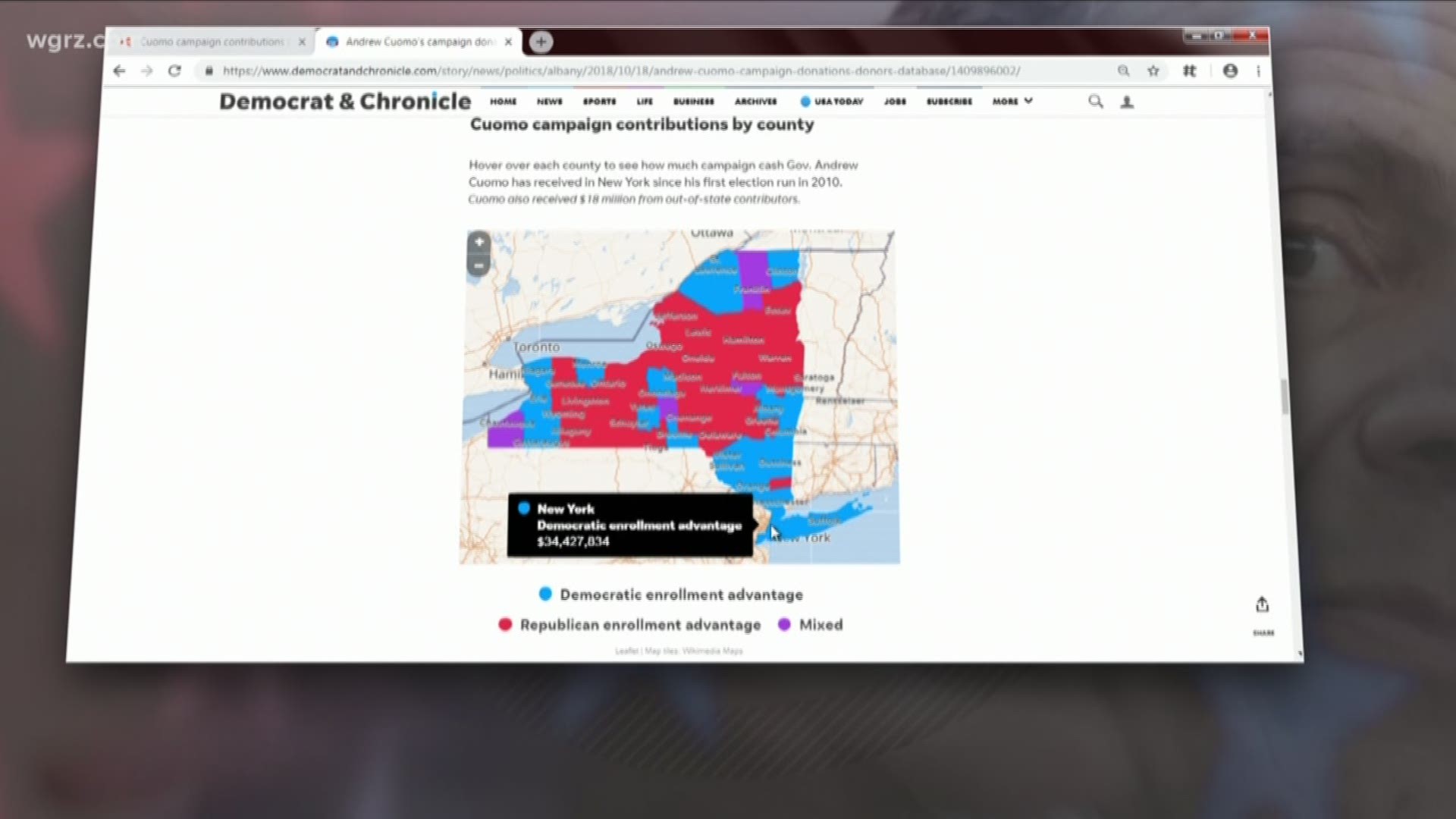

As a result, $34 million of Cuomo's cash since 2010 came from Manhattan; $18 million from out of state; $11 million from Nassau County; $6.6 million from Westchester County and $5.4 million from Albany County.

In Westchester, housing developers and constructors of the new Gov. Mario M. Cuomo Bridge in the Hudson Valley have been among Cuomo's top donors.

Rella Fogliano has built a burgeoning construction company in Westchester, opening several large affordable housing projects in the county.

Fogliano, her relatives and her company, MacQuesten, have contributed $285,000 to Cuomo's campaigns.

The company has benefited from a variety of tax breaks and grants for its buildings, including $15 million in tax-exempt bonds for The Modern, an 81-unit affordable housing complex in Mount Vernon, records show.

Fogliano said MacQuesten is a woman-owned business that is dedicated to building "beautifully designed, affordable apartments in New York" and supports candidates who back her mission.

"All of our support meets the letter of the election law," she said in an statement.

"We will continue to exercise our constitutional right to support candidates and elected officials of our choice that further the cause of affordable housing."

Similar tax benefits were provided by the state to another Westchester developer of affordable housing, Wilder Balter Partners.

The Chappaqua firm and its partners gave $272,500 to Cuomo's campaigns.

Among the state benefits it received was $10 million in financing to redevelop the iconic Reader’s Digest headquarters into 64 mixed-income apartments, as well $5.4 million in state and federal tax credits.

There was no immediate comment from the company.

Major deals, major money

As for the new Cuomo bridge between Westchester and Rockland counties, unions who have contracts on the $4 billion project have pumped about $800,000 into Cuomo's campaign, the website Sludge reported last month.

That included $135,800 from the powerful Building and Construction Trades Council and $55,000 from the Northeast Regional Council of Carpenters, records show. Both unions have endorsed Cuomo.

That's not all: AECOM was a consultant on the project, and the firm vice chairman Dan Tishman, who is part of a New York real-estate dynasty, has been a top Cuomo donor: $160,725 from him and $125,900 from his wife, Sheryl, records show.

Earlier this year, one sizable contribution that drew headlines was $50,000 each that the brothers Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss gave Cuomo in April.

A month later, the state Department of Financial Services gave the twins' company approval for its new virtual currency exchange. In June, records show they each gave an additional $15,000 to Cuomo and co-hosted a fundraiser for him in July.

“They contributed to Governor Cuomo’s campaign because they believe he’s doing a great job,” a spokeswoman for the Winklevoss brothers told the New York Times in July.

Meanwhile, a series of donations made to Cuomo's campaign by Crystal Run Healthcare, the Middletown-based firm, is under federal investigation.

The company is being investigated for 10 separate $25,000 checks from executives to Cuomo in October 2013 that may have been reimbursed by the company through bonuses, the Times Union in Albany reported.

If so, the donations could violate state election law, which bars the use of "straw donors" for campaigns.

It's also an alleged pay-to-play case. In 2016, Crystal Run got $25 million in state grants for projects it was already building, including in Rockland County, the Times Union reported.

Cuomo's campaign has sought to focus on Molinaro's time in office, with Dutchess County lawmakers saying Molinaro should return $330,000 in campaign contributions from 67 companies doing business with the county.

“Not only is Molinaro anti-women, anti-LGBTQ, and ‘A’ rated by the NRA — he’s New York’s biggest hypocrite," Collins, Cuomo's spokeswoman said.

"Molinaro is busy trading favors, taking the nepotism page from Trump’s playbook and giving tax breaks to companies with county contracts."

Fixing the system

New York has long been derided as having one of the most porous campaign-finance systems in the nation.

Individuals have a $65,100 per year limit on campaign contributions to any one candidate, while corporations can give only $5,000 a year per candidate.

But the limits are easy to skirt, and Cuomo's haul could be exhibit A in how simple it is.

Cuomo received $19.7 million from 2,065 donations made by LLCs.

Cablevision, for example, gave Cuomo money through at least a dozen different LLCs and PACs to the tune of nearly $600,000 during his time in office.

The system is more stringent in most other states.

Twenty-two states have an outright ban on campaign contributions from corporations, and New York has the highest contribution limit for governor of any state in the nation, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

State lawmakers and even Cuomo himself have called for stronger campaign-finance laws, including lower limits, public financing of campaigns and closing the LLC loophole.

But Republicans who control the Senate have blocked a number of the initiatives, and Cuomo has drawn criticism for not pushing harder for the changes.

“The governor will continue to lead the fight to close the LLC loophole and is 100 percent focused on flipping the state Senate and winning a Democratic Senate majority so we can enact comprehensive campaign finance reform," Collins said.

Molinaro, too, said he would seek to enact stronger campaign-finance laws if elected.

Critics said that without stronger campaign finance and ethics laws, the opportunity for wrongdoing is pronounced — as evidenced by the convictions of some of Cuomo's top advisers and donors.

"When you have a system where you are relying on a relatively small number of fabulously wealthy donors and you run the government largely outside of public view, the potential for ethical mischief is great," Horner said.

JSpector@Gannett.com

Joseph Spector is chief of USA TODAY Network's Albany Bureau.

The Democrat and Chronicle uses Nixon Peabody’s services for First Amendment work.