As a civilian, it's particularly difficult to cover stories about law enforcement policies and procedures.

I have never conducted a SWAT raid. I've never confronted an armed suspect. I've never investigated a crime, nor have I ever executed a search warrant for crack cocaine.

And, no— I have never encountered an aggressive pit bull in the line of duty.

Given all of that – and the fact that we all hold dogs and animals so closely to our hearts – it's even more difficult to cover the issue of officer-involved dog shootings. It's an emotional topic, but it also requires an understanding of the complicated circumstances in which an officer would fire a weapon at a dog in self-defense.

It does happen. Police officers do shoot dogs, sometimes fatally, and they shoot them everywhere. From Colorado to Texas to California, officers of the law have fired their weapons at dogs in high-profile cases, and the invention of social media has now uncovered a whole new world of public outcry, online petitions and demands for change.

Despite the relentless outcry from Facebook groups across the nation, it's not always such a clear-cut issue. Nationwide, it's impossible to calculate how often police shoot dogs on an annual basis, and it's even more impossible to determine whether officers acted appropriately or inappropriately during any of these encounters. Police have a difficult job – an unimaginable one, in some cases – and they legally have the authority to use deadly force against animals if their lives are in danger.

The same protocol applies to the Buffalo Police Department.

To be frank, when I first filed a Freedom of Information Law request with the Buffalo Police Department in September to obtain weapons discharge records involving animals, I did not expect to receive such a giant stack of papers. The records department provided me dozens and dozens of examples of police shooting dogs, and I knew it would be a challenge to place those incidents into the proper context.

Ultimately, along with WGRZ producer Megan Blarr and a team of a half-dozen photojournalists, we aired our first report in mid-November. Using that data from the records department, we reported that Buffalo Police officers had fired their weapons at 92 dogs in the line of duty since 2011, resulting in the death of 73 dogs. One officer shot 26 of those dogs, killing all but one of them. Chief of Detectives Dennis Richards said his officers did not train for dog encounters, nor did they use alternate tools to tame aggressive dogs. They had failed to follow the lead of dozens of departments across the country, including the New York City Police Department, which shot fewer dogs in 2013 alone than Buffalo Police. For perspective, the NYPD's force – the largest in the nation with 35,000 officers -- is about 46 times larger than Buffalo's police force.

This spring, I teamed with Megan and photojournalist Franco Ardito to once again produce a report about the Buffalo Police Department's training and procedures for canine encounters. After filing a second open records request, I received an even more comprehensive stack of incident reports for all weapons discharges from Jan. 1, 2011 through March 2015.

In Buffalo, we now know that police have shot 102 dogs since 2011. More than three-quarters of these dogs died from their injuries. Perhaps more notably, though, the second set of records indicated that police shot only two dogs between mid-November -- when the story aired -- through the end of March. It's clear: incidents have decreased during this short time frame.

Beginning in mid-April, we contacted the Buffalo Police Department close to a dozen times to arrange a second interview about the new numbers. We had questions. What's causing the drop in officer-involved canine shootings? Has the department implemented new training methods? Will it consider alternate tools to handle dogs in a non-lethal manner? We felt these were important questions for the department to answer.

After five weeks of requesting an interview, the department's spokesman repeatedly denied us access to the Buffalo Police Department's leaders. He finally sent us information on Monday morning -- the day the story aired -- about new training methods for all Buffalo Police officers, derived from a program developed in partnership with the U.S. Department of Justice. The spokesman said the department implemented this video training in late 2014, only a few weeks after our initial story aired in November. As you can see, the number of incidents subsequently dropped during the winter months, for what it's worth.

But we're still left with many questions.

And just as we asked for transparency from the Buffalo Police Department, I would like to also take a moment to outline how we arrived at the initial number – 92 dogs shot – and our current total of 102 dogs.

How We Calculated the Incidents

In September 2014, I filed an initial Freedom of Information Law request with the Buffalo Police Department, asking for two things: 1) policies and procedures relating to the use of aggressive animals and 2) shots-fired incidents involving aggressive animals since 2011. We chose to begin our inquiry in 2011 because it would still offer an expansive time frame to chart progress, but it also would not reach too deeply into the past and risk irrelevancy.

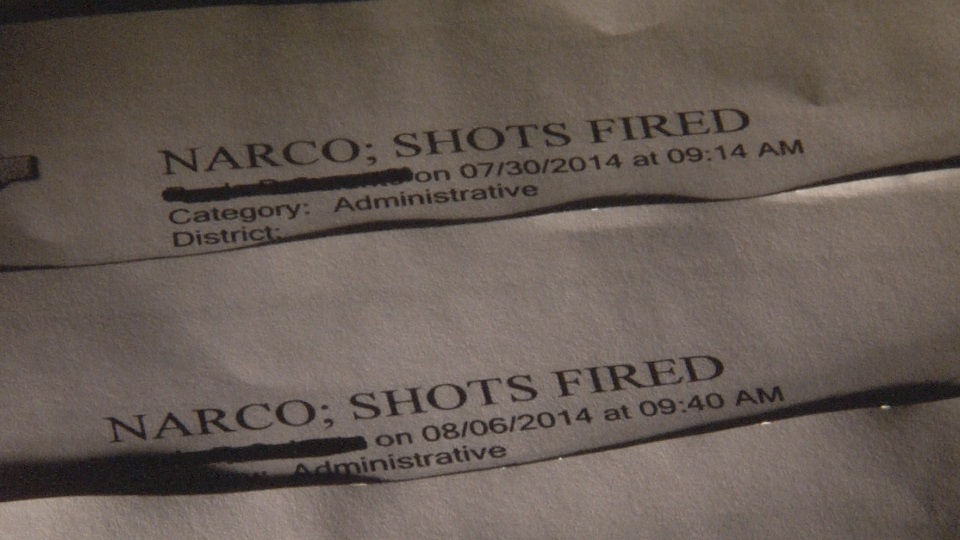

The Buffalo Police Department first provided a copy of its explicit policy for aggressive animals, which authorized officers to use force if they felt they were in danger of death or serious physical injury. Eventually, the records officer then provided a copy of all shots-fired incidents involving animals between Jan. 1, 2011 and Sept. 15, 2014.

When I reviewed the records, I gave some leeway to the department. If the incident report, for example, did not explicitly use the word "killed" or "dead" in some form, I did not count the incident as a fatality. Some incident reports said officers "struck" a dog – or that a dog was "critically wounded" – but I did not feel it was appropriate to speculate. Furthermore, some incident reports indicated that other dogs were present inside of a home during, say, a drug raid, but I did not count them unless the report specifically noted that an officer fired a weapon at the dog.

In all, this first round of records involved 92 different dogs. Seventy-three of these reports noted that the dog "died" or was "killed" in some form.

In March 2015, Megan and I decided to pursue a six-month update.

I filed a new FOIL request with the Buffalo Police Department, asking for all weapons discharge records during the past six months. The records officer gave me even more than I asked for. In late March, I received records for all weapons discharges since 2011, meaning I now had a record of every shot fired by a Buffalo Police officer during the past four years.

As our story outlined, these records brought several new incidents to light.

They indicated only two dog shootings since our story aired on Nov. 14, but the records also revealed five other incidents spanning the months of October and early November of 2014. Although these shootings occurred before our first story aired, we were not previously aware of them because the first FOIL request only spanned through September.

To clarify the new records, I cross-referenced all of these shots-fired incidents since 2011 with the animal-shooting records I already had. Interestingly, I found that the first round of records failed to include three fatal dog shootings from May 2012, May 2013 and May 2014.

The second set of records also failed to include a handful of shots-fired incidents from the first round of records.

I emailed the records officer to make sure that I wasn't missing anything. He told me he had no explanation for why the computer-automated system had jumbled some of the records, and that the overall shots-fired numbers would be accurate if I just simply combined the two FOIL requests into one.

Looking Ahead

Besides dogs, officers have also shot at human suspects and deer (in these cases, it appeared the deer were already critically injured, and officers followed standard protocol) during the past four years, but these cases represent a small minority of the shots-fired incidents. About a dozen times, officers fired their weapons at armed or fleeing suspects, or during traffic stops.

That could make for an interesting follow-up story: it appears that Buffalo Police do not fire very often at humans. Almost all of their incidents involve dogs.

In the end, this all comes back to that concept of "use of force." It's a critical topic, and in Buffalo, it appears "use of force" often involves dogs.

Again, it's impossible for us to determine whether officers acted appropriately or inappropriately in any of these 102 incidents since 2011. I was not there, nor have I ever encountered a leaping pit bull while barging into an armed drug dealer's home. However, not all of these cases involved pursuits of armed suspects. Our November story used the example of Adam Arroyo, whose pit bull died during a police raid in the summer of 2013. In that case, the Buffalo Police Department launched an internal investigation into allegations that officers raided the wrong apartment.

Arroyo was at work during the raid. He said he chained his dog before police shot and killer her.

In November, Buffalo Police declined to provide an update on that internal investigation. This spring, they have refused all interview requests about dog encounters, training, protocols and procedures.

Thus, we are left with only a vague idea of the department's new training procedures, and we have no idea if they will eventually incorporate live animals into their training or if they'll follow the lead of other agencies and seek non-lethal tools to protect against animals.

If they ever change their minds, we would certainly welcome the opportunity to speak on the record with leaders of the Buffalo Police Department.